For several decades, the problem of parting of the ways has received increasing interest of researchers. Dozens of books and hundreds of articles have been written on the subject. Almost all of them show that the separation of Church from Synagogue (Christianity and Judaism) was not a one-time act, but a long-lasting, multi-layered, and diversified process.[1] Judeo-Christians played a significant, I would even say – a decisive – role in this process. They were the ones who argued in favour of Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah expected by the Jews and at the same time they opened the door of the new faith for the Hellenistic and Roman cultures, not linked to Judaism. In this short presentation, I would like to clarify more precisely the meaning of the term “parting of the ways”, point out the role of Judeo-Christians in this process, and highlight the value of prof. Étienne Vetö’s valuable comments on the issue of our interest.

What is “parting of the ways”?

There is a need to define more precisely the technical term “parting of the ways”. This term refers us back to the model of description of the process according to which two religions emerged from biblical Judaism: Christianity and rabbinic Judaism (in this chronological order). In other words, from one “way” two different “ways” emerged. Although the validity of the above view cannot be denied, one should be aware of the fact that Judaism of the first century did not represent one way. Apart from groups traditionally enumerated in handbooks (pharisaism, sadduceism, essenism, zealotry with its radical wing of sicarians, Herodians, scribes, supporters of John the Baptist sometimes described as the Baptists, the Egyptian Therapeutae, and possibly also the Samaritans as the heirs to the Mosaic religion), in Judaism there was also a current associated with apocalyptic literature, then the mystical trend as well as ordinary am-haaretz, that is shepherds not knowing the Law and the poorest people of Palestine.[2] Different faces of Judaism in the diaspora should also be added to the list (for example, the Egyptian Therapeutae).[3]

Therefore, many authors prefer to speak about “Judaisms” in the first century.[4] The ways of practising Judaism were very different and sometimes distant from each other. And from them two separate religions, Christianity and rabbinic Judaism, emerged. What is more, both emphasized the “way,” which means the manner of cultivating the bond with God, and both saw themselves as the “way.” Rabbis developed halakha, in other words, “the way” of the interpretation and application of the Law in everyday life.[5] Similarly, Christianity was seen as “a way” (Acts 9:2) and Christ himself declared that He was “the Way” leading towards God (Jn 14:6). What is more, because the process of disunion between the two religious communities took place in different places and at different times, and was motivated by various factors, therefore many authors prefer to speak of partings (plural) of Judaism and Christianity.

The issue that still calls for in-depth consideration is the complexity of the image of Christianity which was not homogeneous throughout the Roman Empire in the three first centuries. Apart from Judeo-Christians and ethno-Christians, there appeared communities like the Ebionites, the Elcesaites or the Nazarenes.[6] The adherers of Marcion or of Montanus also aspired to the name of Christians; they were excluded from the Church community but it does not mean that the Jews did not to see Christians in them. Hence, among the opinions about the different faces of the Church in the first centuries, one can come across the view represented for example by R. Kraft who prefers to speak of “Christianities” rather than the Christianity of that time. In any case, it is clear that the simple image of the tearing of one canvas of Judaism into two parts (like the tearing of the Temple’s curtain at the moment of Jesus’ death) is not adequate to express the very complex process of the emergence of the two religions.[7]

Role of Judeo-Christians in “parting of the ways” process

The parting of the ways between Church and Synagogue is based on two unquestionable facts: its evolutionary character[8] and the role of Christians descended from Judaism.[9] These two issues are the backbone of first the tension, then the conflict and finally even mutual disfavour and hostility which to a great extent was characteristic of the history of Church and Synagogue in the first three centuries. Tension, conflict and disfavour arose around the person of Christ and interpretation of his role in the history of salvation and around consequences (theological, liturgical and social) resulting from this interpretation.[10]

Generally speaking, the process of creation of rabbinic Judaism and Christianity as separate religions concerns mainly Judeo-Christians. It is hard to speak about the “parting of the ways” of ethno-Christians and the Jews who were not Christian since their ways were never common. Even the most Hellenized Jews in the diaspora (such as Philo of Alexandria) belonged to Jewish communities which gathered on the Sabbath in synagogues and carefully protected their identity as those who were different from “the Greeks.” Pagans known as “God-fearers” could not fully participate in the life of Jewish communities unless they became proselytes. On the other hand, there is no evidence of any Jewish community not believing in Christ that would welcome ethno-Christians with open arms, especially if the latter refused to circumcise. Hence, there was no need for “the parting of ways” of Christians descending from pagan religions and the Jews not recognizing Christ.[11]

There is no doubt that rabbinic Judaism and Christianity started to exist as separate religions in different places and at different times. It seems that at the earliest, the division became reality in Rome when Nero accused the followers of Christ of starting the fire in the year 64, not identifying them with the Jews[12]. The Roman authorities distinguished the two religious groups already at the beginning of the second century. This is evidenced by the issue of Fiscus Iudaicus which, at that time, was not imposed on Christians, and also the issue of persecution. The tax imposed on the Jews by Vespasian after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem was maintained by his son Domitian (81-96) and it encompassed those who “lived the Jewish way” and those who had rejected their Jewish roots.[13] Not only the followers of Christ descended from Judaism (even though they were considered as those who had actually rejected their Jewish identity) but also probably Christians of pagan descent were included in the first group. Since the time of the successor of Domitian, Nerva (96), Christians were exempt from the payment of the Fiscus Iudaicus. The persecution against Christians did not encompass the Jews and vice versa. After the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-135) the edge of policy of the empire was directed against the Jews (Rabbi Akiba became a famous Jewish martyr) and this time the followers of Christ were not bothered. On the other hand, Bar Kokhba himself persecuted Judeo-Christians for the reason that they recognised the Messiah in Jesus, and not in him.[14] In Palestine, Jews and Christians saw each other as two completely separate religious communities after the creation of the Academy in Jabneh around the year 90.[15] Both the Jerusalem Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud confirm that the blessing of minim from the “Eighteen Blessings” prayer was created at that time.[16]

Three possibilities

The question of internal tensions in Christian communities in the first century undoubtedly affected most powerfully the Jewish followers of Christ. They had to decide

(1) if they should join the communities in which an increasingly large group consisted of ethno-Christians or

(2) try to stay within the Jewish communities which did not accept Christ or maybe

(3) to make an effort to develop their own religious structures comprising only Judeo-Christians.

The first possibility, most often confirmed by the New Testament writings, resulted with time in the loss by the Jews believing in Christ of their Jewish identity. The second possibility did not stand the test of time: the Jews believing in Christ were recognized as apostates and excluded from Synagogue by official (rabbinic) Judaism.[17] The supporters of the third possibility, forming communities of Judeo-Christians (related to the Ebionites, the Nazarenes and the Elcesaites) had to find an intermediate status between Christians of pagan descent and Jews rejecting the faith in Jesus as the Messiah[18]. Communities of that type, even if they managed to form coherent religious structures, did not survive long.

The theological and historical analyses have brought to light many nuances linked to this issue. It turns out that there were Judeo-Christians who had departed from practising the Law of Moses (like circumcision, celebration of the Sabbath, observance of religious dietary rules of Kashrut) almost completely, and those who, believing in Christ, still observed the Jewish customs. In this perspective, the Judaizers coming from paganism also played a major role. Although they entered the Christian community from a pagan community, along with the discovery of the new faith they discovered Judaism and leaned towards it, sometimes even more than Judeo-Christians. In addition, various communities whose members were Judeo-Christians or / and Judaizers were characterized by stronger or less strong attachment to the Jewish tradition, customs and rules.

What is more, they did not disappear from the religious scene of the ancient world as quickly as it has been widely assumed in the studies until recently. Researchers dealing with the issue of the parting of the ways essentially concentrated on relations between Christian and Jewish communities in the Mediterranean Sea and thus on the territories where Greco-Hellenistic and Roman cultures dominated. However, the development of Christianity was directed not only to the west of Palestine. The followers of Christ equally quickly brought the Good News to the East, to regions where Semitic mentality dominated. There, especially in Syria, Judeo-Christian communities were developing their activities over a much longer period of time than in Europe; some of them survived even till the beginnings of the fourth century (as prof. Vetö has noticed).[19]

Étienne Vetö about the “parting of the ways”

Among many of the qualities of prof. Étienne Vetö’s paper, I would like to highlight three:

(1) The first seems to be the most fundamental: showing that research on the parting of the ways can make a significant contribution to the grounding and more precise definition of the identity of contemporary Messianic Jewish communities. In the long run, it may turn out that contemporary Messianic Jewish communities can become important environments for Christian-Jewish dialogue.

(2) The second concerns the question of the ordering of terminology. From the methodological point of view, the latest research studies on the emergence of two separate religions from biblical Judaism encounter some terminological difficulties. Researchers in both academic and popular works use in an ambiguous way the terms “Judeo-Christianity,” “Judeo-Christian,” “Judaizers,” “Jewish Christianity” or “Christian Judaism.” The meaning of these terms used by individual authors differs significantly. In some works, the term “Judeo-Christians” is used to refer to the baptised Jews who joined the Church, others use it to describe Christians descending from pagan religions (ethno-Christians) who tended to observe Jewish practices. In the latter case, there is no clear border between “Judeo-Christians” and “Judaizers.”

Prof. Vetö uses the expression “Jewish disciples of Yeshua / Jesus” mainly for designating the first generations, while he prefers “Judeo-Christians” for the later generations. He adds that „the latter are more distinct from other strands of Judaism, and some are not ethnically Jewish.” I think that the acceptance of such terminology would greatly facilitate the whole debate on parting of the ways.

(3) A third and equally important value of prof. Vetö’s paper is that he tries to look at the question of the parting of the ways through the eyes of a Judeo-Christian. Today’s research presents the process of parting of the ways of Church and Synagogue either from the perspective of Christianity[20] or Rabbinic Judaism[21]. It seems that modern scholars have somewhat lost this most important perspective: that of the Jewish disciples of Christ (the first generation) and that of the Judeo-Christians (the later generations). This observation seems to be an important clue for contemporary Christian-Jewish dialogue: in order for this dialogue to become truly fruitful, it is necessary, above all, to listen to the voice of contemporary Messianic Jewish communities[22].

***

[1] Wayne A. Meeks after analysis of the texts of the New Testament, in view of relationship of Church and representatives of Judaism, comes to a simple conclusion: “The path of separation, then, was not single or uniform”; Wayne A. MEEKS, In Search of the Early Christians. Selected Essays, New Haven – London 2001, 132.

[2] Andrzej MROZEK, Chrześcijaństwo jako herezja judaizmu, The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture 5 (2013) 10. The author uses the term “heresy” in the same sense in which it was used in the writings of Jewish historians of the first century and in the New Testament: Josephus and Philo used the term hairesis “to determine not only philosophical schools but also religious groups within Judaism such as the Essenes, the Sadducees and the Pharisees. The Meaning of the term hairesis in the New Testament is close to that which we find in Hellenistic texts and in Judaism”; ibid., 12.

[3] Torrey SELAND, Once More – The Hellenists, Hebrews, and Stephen: Conflicts and Conflict-Management in Acts 6 – 7, in: Peder BORGEN, Vernon K. RROBBINS, David B. GOWLER (Hg.), Recruitment, Conquest, and Conflict. Strategies in Judaism, Early Christianity, and the Greco-Roman World, Emory Studies in Early Christianity, Atlanta 1998, 179-200.

[4] Bruce Chilton, Jacob NEUSNER, Judaism in the New Testament. Practices and Beliefs, London – New York 1995, XVIII.

[5] In a similar way, the residents of Qumran saw their community as “the way” (1QS 4,22; 8,10.18,21; 9,5).

[6] More about these groups, see: Karl BAUS, Von der Urgemeinde zur frühchristlichen Grosskirche, Handbuch der Kirchengeschichte 1, Freiburg – Basel – Wien 1963; Matt JACKSON-MCCABE, Ebionites and Nazoraeans: Christians or Jews?, in: Hershel SHANKS (Hg.), Partings. How Judaism and Christianity Became Two, Washington 2013, 187-205; Petri LUOMANEN, Ebionites and Nazarenes, in: Matt JACKSON-MCCABE (Hg.), Jewish Christianity Reconsidered. Rethinking of Ancient Groups and Texts, Minneapolis 2007, 81-118; Simon C. MIMOUNI, Réflexions sur le judéo-christianisme, in: Jacob NEUSNER (Hg.), Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults. Studies for Morton Smith at Sixty, II, Early Christianity, Leiden 1975, 53-76; Richard BAUCKHAM, The Origin of the Ebionites, in: Peter J. TOMSON, Doris LAMBERS-PETRY (Hg.), The Image of Judaeo-Christians in Ancient Jewish and Christian Literature, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 158, Tübingen 2003, 162-181; Joseph VERHEYDEN, Epiphanius on the Ebionites, in: Peter J. TOMSON, Doris LAMBERS-PETRY (Hg.), The Image of Judaeo-Christians in Ancient Jewish and Christian Literature, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 158, Tübingen 2003, 182-208.

[7] Mariusz ROSIK, Church and Synagogue (30-313 AD). Parting of the Ways, European Studies in Theology, Philosophy and History of Religions, Berlin – Bern – Bruxelles – New York – Oxford – Warszawa 2019, 466.

[8] Martin GOODMAN, Modelling the “Parting of the Ways”, in: Adam H. BECKER, Annette YOSHIKO REED (Hg.) The Ways That Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Text and Studies in the Ancient Judaism 95, Tübingen 2003, 122; Waldemar CHROSTOWSKI, Żydzi i religia żydowska a Maryja Matka Jezusa, Salvatoris Mater 2 (2000) 1, 219; Andrew S. JACBS, The Lion and the Lamb. Reconsidering Jewish-Christian Relations in Antiquity, in: Adam H. BECKER, Annette YOSHIKO REED (Hg.) The Ways That Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Text and Studies in the Ancient Judaism 95, Tübingen 2003, 98.

[9] James G.D. DUNN, Christianity in Making, 2, Beginning from Jerusalem, Grand Rapids–Cambridge 2009, 133-138.

[10] Mary C. BOYS, Doing Justice to Judaism: The Challenge to Christianity, Journal of Ecumenical Studies 49 (2014) 1, 107-108; Peter LANDESMANN, Anti-Judaism on the Way from Judaism to Christianity, Wiener Vorlesungen: Forschungen 5, Frankfurt am Main – Berlin – Bern – Bruxelles – New York – Oxford – Wien 2012, 51-54.

[11] Mariusz ROSIK, Church and Synagogue (30-313 AD). Parting of the Ways, 465-466.

[12] “Separation of Christians from Jews, then, must have started extremely early in the imperial capital, if within a generation of the death of Jesus of Nazareth neither the common people nor the authorities had any difficulty in distinguishing between the adherents of those two closely related ‘superstitions’, as elite Roman writers disparagingly referred to them”; David M. WILLIAMS, Jews and Christians at Rome: An Early Parting of the Ways, in: Hershel SHANKS (Hg.), Partings. How Judaism and Christianity Became Two, Washington 2013, 152.

[13] Marius HEEMSTRA, How Rome’s Administration of Fiscus Judaicus Accelerated the Parting of the Ways between Judaism and Christianity. Rereading 1 Peter, Revelation, the Letter to the Hebrews, and the Gospel of John in their Roman and Jewish Context, Groningen 2009, 14. According to some authors the tax applies to every Jew aged between three and sixty; Martin GOODMAN, Diaspora Reactions to the Destruction of the Temple, in: James D. G. DUNN, Jews and Christians. The Parting of the Ways. A.D. 70 to 135, Grand Rapids 1999, 30.

[14] Richard BAUCKHAM, Jews and Christians in the Land of Israel at the Time of Bar Kochba War with Special Reference to the Apocalypse of Peter, in: Graham N. STANTON, Guy G. STROUMSA (Hg.), Tolerance and Intolerance in Early Judaism and Christianity, Cambridge 1998, 228-231.

[15] Daniel Boyarin of the University of California, Berkeley, believes that researchers interpret the “Jabneh effect” incorrectly: “All of the institutions of rabbinic Judaism are projected in rabbinic narrative to an origin called Yavneh. Yavneh, seen in this way, is the effect, not the cause”; Daniel BOYARIN, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity, Philadelphia 2004, 48.

[16] William HORBURY, The Benediction of the Minim and Early Jewish-Christian Controversy, JTS 33 (1982) 19-20; Jacob MANN, Genizah Fragments of the Palestinian Order of Service, Hebrew Union College Annual 2 (1925) 306.

[17] Mirosław WRÓBEL., Birkat ha-Minim and the Process of Separation between Judaism and Christianity, The Polish Journal of Biblical Research 5 (2006) 2, 99–120; Frideric MANNS, John and Jamnia: How the Break Occured Between Jews and Christians c. 80–100 A.D., Jerusalem 1988.

[18] Stanley JONES, Pseudoclementina Elchasaiticaque inter Judaeochristiana: Collected Studies, OLA 203, Leuven 2012.

[19] Annette YOSHIKO REED, „Jewish Christianity” after the „Parting of the Ways”. Approaches to Historiography and Self-Definition in the Pseudo-Clementines, in: Adam H. BECKER, Annette YOSHIKO REED, The Ways That Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Text and Studies in the Ancient Judaism 95, Tübingen 2003, 189–231.

[20] John G. GAGER, The Parting of the Ways; A View from the Perspective of Early Christianity: ‘A Christian Perspective’, in: Eugene FISHER (Hg.), Interwoven Destinies: Jews and Christians Through the Ages, New York 1993, 70-73.

[21] Martha HIMMELFARB, The Parting of the Ways Reconsidered: Diversity in Judaism and Jewish-Christian Relations in the Roman Empire. ‘A Jewish Perspective’, in: Eugene FISHER (Hg.), Interwoven Destinies: Jews and Christians Through the Ages, New York 1993, 47-61.

[22] Mariusz ROSIK, Church and Synagogue (30-313 AD). Parting of the Ways, 550-551.

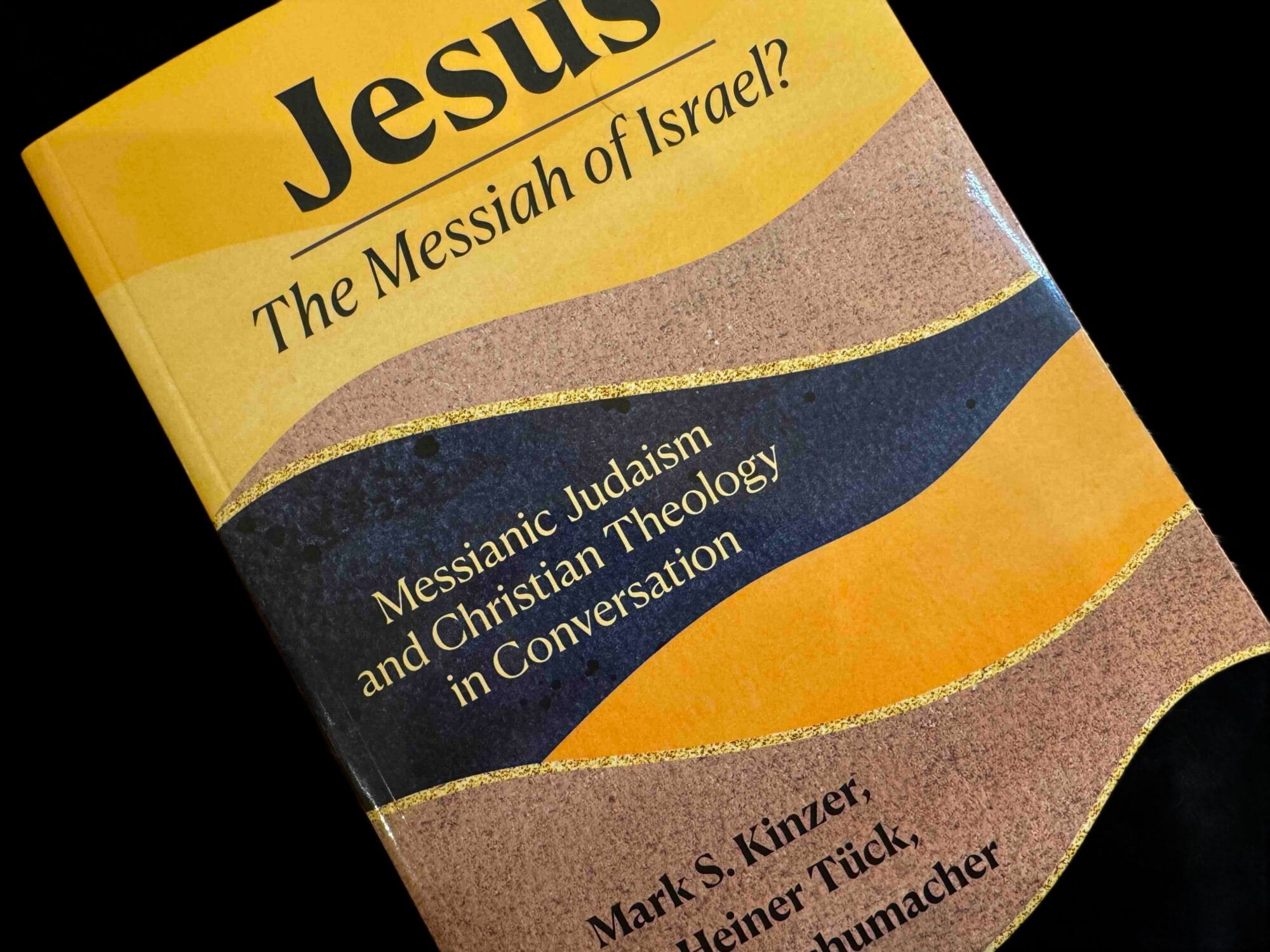

„Response to Étienne Vetö: 'Assessing Jewish Christianity'”, in: Jesus. The Messiah of Israel? Messianic Judaism and Christian Theology in Conversation, ed. M.S. Kinzer, T. Schumacher, J.-H. Tück, J.E. Patrick, Herder, New York 2025, pp. 257-267.

Polub stronę na Facebook