fot. M. Rosik

Love means to learn to look at yourself

The way one looks at distant things

For you are only one thing among many.

Czeslaw Milosz

Frédéric’s world rocked when, in 1837, he got closer to George Sand. The relationship which lasted for almost a decade and came to an end due to the growing hostility of the writer’s son is considered to have been the happiest time in the life of the pianist. The contemporaries regarded the affair as scandalous. When the vanguard author of popular novels appeared on the artistic path of Chopin, six years her junior, he was still deeply affected by the breakup of his relationship with Maria Wodzińska. The parents of the latter had considered the pianist as an inappropriate candidate for a husband of their daughter because of his poor health. Chopin was devastated – he yearned for affection and found it in the arms of solicitous George. When they met at the home of Marie, Comtesse d’Agoult, George was thirty-two. The composer bent then over a table laden with crystal glasses that shimmered with ruby wine and briskly confessed to his interlocutor: “What an unpleasant woman.” He quickly changed his mind, however. There was that secret in the gaze of George which is hidden in the souls of mysterious women, beautiful like angels, inaccessible like volcanoes before an eruption, who enchant only those they choose to bewitch. A few months later, during an evening at the home of Charlotte Marliani, a note from Sand, smelling of the writer’s perfume, was discreetly passed to Frédéric. The blue ink immortalized the straightforward declaration: On vous adore!In September 1838, the French novelist confessed to her friend Eugene Delacroix who was at that time sketching a joined portrait of the two: “If in one hour’s time God were to send me to death, I would not complain, as three months have passed in undisturbed intoxication.”

Almost two years after their first meeting, the writer and the musician departed for Majorca, with heads full of fond dreams. The island, a diamond jewel bathed in azure waters, was, for a time, going to become their home. And not only in the physical sense. They were looking for solace and feeling of safety, for unshakeable faith in the accuracy of decisions already made and for freedom which stems from the sense of having one’s own place on earth. That was meant to be the Majorca of George and Frédéric. Today, I’m travelling across the island, trying to imagine and recreate the atmosphere of that time.

FIRST DAYS IN PALMA

In the morning, when I reach the capital, the city is flooded with sunshine. White buildings and stately churches sparklE in the sun. Parks and streets, luxurious air-conditioned shops and picturesque lanes filled with tiny enchanted cafés are all floating in the yellow light. In the air, the scent of hydrangea is mixed with the smell of sea breeze. Did the city look similar almost two centuries ago? Did it exude the same atmosphere? Was it engulfed in the same climate? In 1838, Chopin wrote about the capital: “I am in Palma between palms, cedars, cacti, olives, oranges, lemons, aloes, figs, pomegranates… The sky is like turquoise, sea like azure, mountains like emerald, air like heaven.” We can only regret that hardly anybody writes in such a beautiful manner today but the other thing to be noted is the fact that Chopin’s stay in Valldemossa, where he moved soon afterwards, did not seem to be so very romantic.

Chopin arrived in Palma with his partner and her two children, Maurice and Solange. The ship El Mallorquin did not need much time to reach the gentle green and yellow shores of the island. The two artists did not stay long in the capital; the accommodation they had rented turned out to be too expensive. Besides, the composer’s illness forced them to leave the uncomfortable, small flat as the owners were afraid of catching an infectious disease.

Strolling along the streets, I wonder how much the city has changed since that time. The white, flat roof houses have been here for centuries. The churches were probably well-tended, the belfries whitewashed with lime every summer. Open-air markets full of figs, oranges, coconuts, dates, nuts and dried fruit and glittering with all colors of the rainbow must have been here, too. As well as the fish stalls. The Mallorcan music, harmoniously combined with the southern temperament, creates and completes a truly unique atmosphere of the place.

The Gothic cathedral La Seu proudly towers above the city walls. Its construction started in the thirteenth century and lasted for almost three hundred years while the ornamentation was completed as late as in 1914. Thus, Chopin did not get to know the flamboyant typography of the magnificent building situated majestically at the point of the city which allows its soaring, slender, white sandstone silhouette to be clearly visible from the sea. He obviously could not admire the chandeliers surrounding thin columns, introduced here by Gaudi. Sunrays stream into the bronze of the nave through the largest rose window in the world, at twelve meters in diameter. The light is scattered over the walls and the floor, its streaks vibrating in the gorgeous dance. It decomposes into hundreds of colors and fills the interior like a ballet dancer on the sacred stage of the stone edifice. In such atmosphere thoughts must ramble high.

Having left the cathedral, behind the brass door, I’m heading right and, squeezing through narrow streets that bear graceful names of Sant Roc, Zanglada or Morey, I make my way to the second temple. The church of Santa Eulàlia all of a sudden materializes in front of me. There are two entrances leading into the three-aisle building. The Baroque altarpiece once witnessed an unusual scene: Ramón Llull, one of the island’s favorite beatified, entered the church on a black horse in pursue of his beloved. Before renewing his bond with the Church, Ramón could have been regarded as Chopin’s predecessor. He had also fallen in love with a married woman, but the difference was that it was him and not her who had already been the parent two children. After his conversion, whose motives we can only guess, he spent many years studying Arabic in order to start, at the age of sixty, his mission of converting Muslims in Africa and in the Middle East.

Even during a short stay in the capital, the presence of Jewish community cannot have escaped Chopin’s notice. Its history on the island dates back centuries. Until the end of the fourteenth century, the Jewish community was held in high esteemmainly due to their choice of professions. The followers of the God of covenant were predominantly goldsmiths. The Jews were known as exceptionally skillful jewelers. Until today, the mystery atmosphere of that time can be felt in Carter de Arginina, a little street filled with jewelry stores and workshops. With time, however, Jews were more and more often accused of counterfeiting coins and of inhabiting the land of Saracens. The fact that they did not care about integration with the rest of Mallorcan community was another sin. They differed in the way they spoke, ate, dressed, in their religious rites and social status.

Xuete are descendants of Mallorcan Jews who, at the time of the Inquisition, were persuaded to convert to Catholicism. Many of them accepted Christianity only as a cover for their Jewish faith and practice. To avoid persecution and rejection by the rest of the community, they admitted to being Christian on the outside; in their own circle, however, they still followed Jewish religious observances. There were of course some who really converted to Catholicism, but their life on the island was not any easier. They could neither leave the ghettoes nor get married outside the community of other xuete.Catholic priests of Jewish descent were allowed to celebrate Holy Mass in the cathedral in Palma as late as in the eighteenth century. Until this day a unique sign of the community of the converted Jews can be found in it: a colorful stained-glass window designed in the shape of the Star of David.

UNREMEMBERED CUSTOMS

Thirty years ago no one even thought of locking the door when going shopping or taking a vacation. The key was left in the door for the postman to leave the mail or newspapers on the living room table, next to electricity or gas bills delivered by office workers. The latter frequently helped themselves to drinks and collected gratuities left by the homeowners. Theserenos have also disappeared from the island. They were a kind of guards who wandered the streets at night, every now and then shouting out the hour. Thanks to them, the inhabitants of the island did not have to get up and switch on lights to see what time it was. Hearing the calls, they woke up for a while – air-conditioning was unknown yet so the windows were always open – and decided whether it was already time to get up or if they could still rest in the arms of the goddess of the night. Serenos also had a lot of understanding for men on their way home from canteens and lost in their own dream worlds. Those who suffered from dizziness due to excess consumption of heavenly scent red wine were led home, assisted while opening the door and even put to bed. The serenoswere particularly sympathetic to the broken hearted, all those individuals seeking refuge from heartache in the divine drink, purple in color, clear like a ruby. For what else can be done at the first moments when it dawns on you that your love has been rejected? Then, birds stop singing, the sun fades, buds no longer develop into flowers, the sky does not look so blue and time seems to come to a halt…

A custom known as camilla is gone, too. The name refers to a round table covered with a cloth big enough to reach the ground. On chilly autumn nights or rainy days women would place a container full of live charcoal beneath a camilla so that all those entering the house could sit at it, tightly covering their legs and deriving pleasure from the overwhelming warmth. They could then talk at length, spill ink writing long letters, read local newspapers or discuss new residents and famous tourists. That was a time when tourists were scarce on the Balearic Islands; thus, they would often hear from the islanders mi casa es su casaand in the morning, on the doorsteps leading to their apartments, they were likely to find wicker baskets filled up with fruit.

What has also gone into oblivion are piropos, whispers, sweet little compliments paid by men to women who happened to be passing by. Only thirty years ago, on Sunday mornings, one could still spot slender ladies leaving the white churches with prayer books in their hands. Their heads were usually covered with special bonnets, their dresses glowed with freshness and rustled flirtatiously, and the faces wore the expression of dignity and radiance at the same time. When a female city dweller did not hear men whispering behind her back, or, to be precise, did not hear one word – piropo– it meant it was time to immediately take care of one’s looks. But the rule was not to react to the whispering in any way – neither with a nod nor with a glance or a squint. This was what local tradition demanded. The more beautiful the addressee of the piropowas, the more delighted and fanciful the sighs of admiration were. A lady could, for instance, hear: ‘If beauty is a sin, you will never be forgiven’ or ‘Wherever you go, flowers start budding’ or ‘Now I know heaven exists; I’ve seen an angel.’ But we will never know the secret of thepiroposthat enamored Chopin whispered into the ear of George Sand. We can only imagine that they were filled with the most refined music that resounded with inspiration in the writer’s soul and echoed silently on the pages of her emotion-charged novels.

Chopin was deeply in love when he arrived in the island but, since the couple were staying at a cloister, it was impossible to share a room with George. It is true that the Carthusian monastery had already been closed for three years due to the cassation of the order but the rooms were distributed by the only monk left in the town. The lovers found consolation in the fact that they only paid thirty-five pesetas for the whole year which was, at the time, an incredibly low price. They moved from Palma to Valldemossa when the host who had rented the room to them had discovered that the composer suffered from tuberculosis. They were immediately given notice to quit. Their stay in Majorca was an escape anyway, mainly from the gossip of Parisian artistic circles. They also hoped for improving health of both the musician and George’s fifteen-year-old son. Even though Chopin did not lament in his diary over the fact that he had been given a separate cell, it is clear that he would have preferred to sink into the soft arms of his French lover rather than to sleep alone in a cold room, on an uncomfortable bed, with a wooden prie-dieu placed next to it. Well, not every love can be fulfilled… Anyway, the Romantic with flowing hair and poor health complained about the quality of his accommodation: “My cell is shaped like a big coffin, the enormous vaulted ceiling covered with dust, the window small. In front of the window are orange trees, palms, cypresses; opposite the window there is my camp-bed.” Today, many dreamers would feel happy with the idea of a sentimental little window overlooking a garden… The composer’s intention was to heal in Valldemossa his illness-stricken body; he hoped that the climate of Majorca would be beneficial to his health. The assumption was correct but he had not expected that the poor monks would offer him a mold-infested cell. And, unfortunately, such living conditions do not necessarily improve health of brilliant musicians.

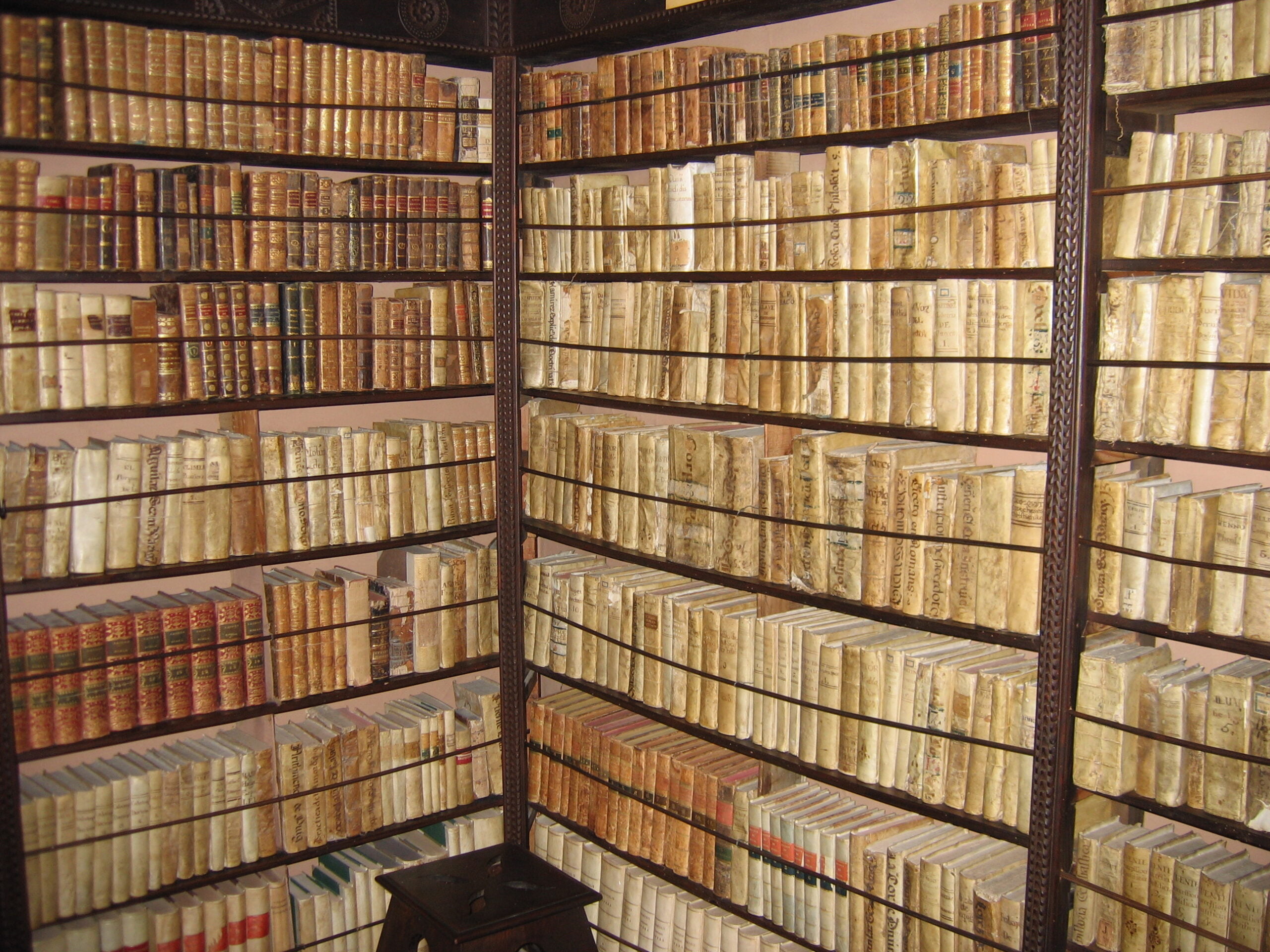

Today I am looking with fondness at the places where Chopin and Sand spent several months of their lives. A small but magnificent library still smells of leather; it is filled with antique books, encrusted furniture in all possible shades of bronze, simple household equipment, spacious wardrobes, huge chests of drawers, an elegant desk… There is also a cloister apothecary abounding in mysterious vials, colorful bottles, containers of every possible size and shape, boxes and ampoules. As if some invigorating or poisonous potions had been prepared here according to secret recipes… All of these recreate the atmosphere of the old days and probably not much has changed for almost two centuries. Through open windows framed with wooden shutters, silent music of nature is entering the interior: the cheerful twitter of birds, the soft rustle of trees in the garden. Ideal conditions for creative work, for composing, for writing… Or they would have been ideal had it not been for Chopin’s failing health and tensions provoked by teenage Maurice who did not approve of the relationship between his extrovert mother and the outstanding pianist.

Nevertheless, there were also some positive aspects of the stay of the composer and the writer on the island. At the beginning, the infatuated couple loved the little town, picturesquely situated in the middle of the mountains. In his letter to Julian Fontana, Chopin even called it “the most beautiful situation in the world.” In “Un hiver à Majorque” Sand declared that sensibility and reserve were two dominating features of character of the inhabitants of the island. But, as a woman, she was not very constant in her opinions. In other places of the same book she disparaged the Mallorcans as “monkeys” and thieves, and then added that things might have gone differently, had the artists bothered to go to church… That could have stopped the locals from throwing stones at them when they were passing by. Apart from the absence from the Sunday Mass, George Sand committed other grave sins: she was one of the first women to smoke cigarettes and she wore trousers. What a true pioneer-feminist!

MISALLIANCE BETWEEN MUSIC AND LITERATURE

After leaving Chopin’s museum, I take a stroll along the winding streets of Valldemossa. It’s getting dark. Chilly evening breeze gently glides over my face. In the tiny windows of the small houses I can see the first lights. Life is slowing down but it does not mean it is quiet. Street cafes and restaurants are filled with people. Lanterns are being switched on. When I am passing by one of the lovely coffeehouses, all covered in flowers, I can hear the confessions of Diana Krall: I remember as youtold me: Love is touchingsouls. The soul of Frédéric, quavering with sounds, and the soul of George, so sensitive to words, touched and met in love. Love forbidden and unplanned. Condemned but so very real. As real as the music of Chopin and the books of George Sand. As subtle as the preludes composed here. Fragrant as the black words of the book that still smells of the printing ink.

The love was real and impossible at the same time. Both adjectives reflect the atmosphere in which the lovers and George’s children spent their days. There were moments of happiness but also tensions, confessions of love and arguments. Affection mingled with anger and forgiveness, the sense of helplessness in the face of the illness was mixed with creative exultation. Such emotions can be read by psychologists in the drawings of Maurice. His objection to the relationship of his mother with the composer grew with age. The boy’s pictures, revealing his artistic talent, can be admired in the glass showcases displayed in the former cells of the Carthusian monks.

In Valldemossa, Chopin complained about the lack of instrument. His own Pleyel had been damaged at the customs office and a new piano, sent from France by a friend, arrived in the island twenty days before his leaving it. In despair, he complained in a letter: “Only today I have received a message that on 1 Decemb. in Marseille the piano was loaded on the merchant ship. The letter from Marseille was posted 14 days ago. I hope the piano will spend winter in the port or anchored (because here nobody moves when it’s raining) and that I will receive it only when I will be leaving Majorca, what makes me happy because apart from 500 franks of the duty I will have the pleasure to wrap it up for the journey back. For the time being my manuscripts are asleep, and I can’t sleep, I only cough.”

Despite difficulties, on the rickety cloister piano, he composed the “Rainbow” Prelude, corresponding in its mood to the moldy cell of the consumption-stricken virtuoso. He sometimes composed music in his thoughts, while taking a walk. But he had to hear it outside his head, too. He longed to hear the sounds one after another, live, to write them down in his notebook. His fingers, not very long but pliable and swift, couldn’t wait to feel the touch of the black and white keyboard. Chopin was totally absorbed by the process. Shortly afterwards, during the stay in Nohant, George Sand described it in the following manner: “His creation was spontaneous, miraculous. He found it without searching for it, without foreseeing it. It came to his piano suddenly, complete, sublime, or it sang in his head during a walk, and he would hasten to hear it again, by tossing it off on his instrument. But then would begin the most heartbreaking labor I have ever witnessed. It was a series of efforts, indecision, and impatience to recapture certain details of the theme he had heard: what had come to him all of a piece, he now over-analyzed in his desire to write it down, and his regret at not finding it again ‘neat,’ as he said, would throw him into a kind of despair. He would shut himself up in his room for days at a time, weeping, pacing, breaking his pens, repeating and changing a single measure a hundred times, writing it and effacing it with equal frequency, and beginning again the next day with a meticulous and desperate perseverance. He would spend six weeks on one page, only to end up writing it just as he had traced it in his first outpouring.”

ENCHANTED ISLANDS

Chopin left Majorca on February 13th, 1839. The next day, his ship reached the sunlit port in Barcelona and he set foot on the continent. On the island, Chopin had been seeking home. He had been searching for solace, refuge, a place where he could work, for the feeling of safety and for artistic inspiration. Meanwhile, a malady stealthily crept into his life and he had to struggle with in not only on Majorca but for the rest of his days. What was left after the stay on the island were the memories of some beautiful moments spent with the beloved and the Preludes. The most famous one is the “Raindrop” Prelude. The pianist did not have to look for inspiration very far since it rained most of the time during his several-week stay at Valldemossa. What has also remained are the memories of George Sand included in her novel Un hiver à Majorque.

For many people, however, this island is their home. I’m thinking about it seated aboard a comfortable plane which in a few moments is going to get off the spacious ground of the airport in Palma. When the flight begins, I put on headphones to be submerged in the sounds of the organ and the violin. The CD recorded by brilliant Polish musicians is entitled Light. It combines words and sound, music and lyrics. Even if the relationship between Frédéric and George had to come to an end, what has still remained are the virtuoso sounds and words, captured in their compositions. Engrossed in the text and music, I look out of the window. Majorca has already been reduced to a little spot on the blue waters of the sea. “On my island, a bird does not fly off when hearing somebody’s steps, but it sings its song louder and even more gracefully. On my island, you can still hear delicate sounds of music. It is loud enough to teach the soul about beauty and soft enough not to intrude on your thoughts. On my island everything turns into a prayer: raindrops splashing against my face and mist hovering over a valley, a rainbow stretched above in the blue sky and the bright glance of friends who are able to listen, wind playing with my hair and the light of a candle reflected in the hollow of the glass of red wine. ‘There is a season for everything, a time for every occupation under heaven.’

On my island there is a house. A real one, with a massive door, wooden shutters and mallow flowers along the fence. This is the house of light. During the day, its beams stream inside through the open door, conquer the stubbornness of the dark floor and change it, right from the doorstep, into a luminous carpet. In the night, through the gaps in the shutters, the yellow streaks of light seep into the thicket of trees. A trail of pale smoke above the thatch roof tells to the sky the story of light that is lurking at the bottom of the chimney. The shutters batter in the wind. Rain washes away the coating of summer dust. The enchanted house gives shelter to ordinary people. Every night, they stand in line for the dawn. On my island, time weaves everyday life from colorful threads. It tangles laughter with crying, love with betrayal. But tears dry up faster here and infidelity does not hurt that much. What matters on the island is the present moment. The past does not belong to us anymore. Ours are only the conclusions we draw from it. The future has not arrived yet. It will come and say: That’s me, the present. Here, in time, there is a constant now. And it is up to us what we do with it. A moment is not likely to repeat itself. It has never happened before and it is not going to happen again. It is offered only once. Only now.

On my island, there are boundless golden deserts with tiny little oases in each of them. Gardens blossom there, painted green, yellow, red and purple. Their colors are intensive. Their presence longed-for. The heat of the day is mixed with the black chill of the night. Nights in the desert swell with fear. Still, no fear is deep enough or none of the nights dark enough not to be able to see at least a single star among the clouds. And latch on to it. And believe that the spark may ignite flame.

We all create our islands. There, we build our houses. In the houses, we open the windows. And we look out the windows, awaiting those who should come so we could love them. So they could love us…”

trans. M. Konopko

Polub stronę na Facebook