There are flowers

that bloom even in winter

Victor Hugo

“We can assure your majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would even be remarkable in Spain”

– such were the words that Francisco Pizzaro used in his letter to King Charles V of Spain to depict the wonders of Cuzco. And Cuzco is an ideal starting point for a trip to Machu Picchu. When, several years ago, I read these words in one of the issues of National Geographic, I thought to myself: I have to check it! And now I am flying to Peru!

Pizzaro described an old town which today towers over the country situated in the western part of South America. Three main geographical regions of Peru meander side by side like three parallel colorful ribbons stretched out along the blue waters of the Pacific. Contrary to the name of the ocean, life in the hot melting pot of deserts, mountains and the jungle is not peaceful at all. City lovers have settled along the coast. Overworked campesinos, farmers, have chosen the mountains as their home. Only very few have decided to pursue the hunting lifestyle of the Amazon. A constant struggle with wild nature, the fight for survival, the combat to obtain food, to subjugate the wild terrain, the impenetrable mountains and immeasurable lakes, to subordinate them to human will and control has marked hundreds of years of human existence in this land. Difficult living conditions, in particular in the mountains and tropical forests, are, however, compensated by the beauty of the landscape.

But can beauty be captured in words? Can we find proper vocabulary to describe intoxicating scents or soothing hues, enclose in a phrase a sweet fragrance or an explosion of color? Is it possible for human language to depict a majestic silhouette of rolling hills, of vast landscapes, of open spaces and boundless skies, of endless meadows or a jungle that stretches away for hundreds of kilometers? One might ineptly try to describe smells or hues, shapes and impressions but, in the end, beauty anyway defies any such attempts. It yields, however, to the feeling of someone who experiences it. It is embedded in the heart and memory for ever.

A CITY DESCENDING INTO OCEAN

With such thoughts lingering on in my head, at the beginning of February, that is to say, in the middle of a hot summer, I am landing in Lima. The encounter with the capital highlights various types of contrasts in the mind of somebody arriving here for the first time. The city descends into the waters of the ocean and climbs gently up the hills. The luxury district of Miraflores exists here next to the slums surrounding the town. This is the city of the rich and the poor, Indians and white people, the descendants of Chinese immigrants and the wave of newcomers arriving from almost all over South America; the city of fear and love, high hopes launched into the air like carnival fireworks and the mundane will to survive that crawls close to the ground.

Out of the twenty-six million inhabitants of Peru, eight million have chosen Lima as their home. The dominating language of the capital is Spanish, but there are also Indians who speak Quechua or immigrants from around Titicaca where Aymaran languages are spoken on everyday basis. The mixture of tongues very well corresponds to the slightly chaotic nature of the metropolis that has spread its boughs on the coast of the Pacific. The city always bustles like quicksilver, it is humid like a steam bath in the summer, in the evening luring with lights like a disco under the stars. Colonial buildings mix up with Incan pyramids and everything is coated in sticky residue of car fumes. This is the city’s everyday reality.

CHILDREN OF PARADISE

‘Paradise’ is located on the outskirts of Lima, in Huachipa. I’m heading toward it straight from the airport; this is my first stop on the way to Machu Picchu. El Paraiso is the name of one of the slums where padre Bogdan, a tall, handsome man who used to wrestle with human needs in many missionary places, has been running his mission for several years now. He has been waiting for me outside the wide sliding door of Lima Airport. Now my backpack is already in the boot and we are on our way to Paradise. The journey takes one hour; after the arrival, I can still feel dizziness caused by the long flight, jet lag and air-conditioned lounges. The Paradise has spread its boughs on barren hills. There is no water here, no vegetation, and everything is covered with powder and dust. The ash hovering in the air clogs your mouth, penetrates your eyes, your ears, your nose, leaves you with the feeling of dryness. The forty degrees of heat make everyone swelter.

Still, I look around with great curiosity. In El Paraiso there is a chapel. A real one, built of stone and not – as in many surrounding settlements – constructed of cardboard and cane. A group of children shows up out of nowhere the moment I enter it. They look at the newly arrived gringos with big eyes, a bit frightened but intrigued. These kids are lucky: they live close to Lima so they go to school. Reportedly, in the interior, there are places where more than half of the population is illiterate. Here, the alphabet and the intricate art of reading is taught by Maria who has recently left prison. She has long, plaited, raven-black hair and a simple red dress. I wonder what bad things this fragile creature could have done to have ended up behind bars. Of course, I do not dare to ask. A Catholic mission is a good workplace for Maria. Using a bizarre mixture of Italian and Spanish, I try to find out how people can exist here practically without water. And in what way these wild settlements are erected.

The girl tells me about tank trucks which arrive here every week to supply inhabitants with water. But it takes just a moment and the conversation turns to broader issues. Maria says that people manage to settle in the vicinity of Lima by resorting to a certain trick. The story is picked up by padre Bogdan. Touching his beige hat with the tips of his fingers, he starts talking about invasion, a somehow deceitful but popular way of taking over new land. If someone owns a large plot of land in the immediate proximity of Lima, one night or another he might expect such an ‘invasion.’ It could only take a few hours for several or several dozen families to move into such an area with all their possessions. If the owner does not manage to get rid of them in the course of two days, the case ends up in court. But courts are corruptible and such cases may drag on for years here. That is why it is easier for the landowner to make a deal with the intruders and sell the land to them for peanuts. He loses a lot in this way but he would lose even more in the court proceedings. Que vamos a hacer? – ask the landowners. “What can we do?” Many new settlers, organizers of the “invasion,” enjoy the possession of the property deed only for a short moment: they find a buyer and sell their plot of land for a much higher price to someone who, having abandoned the mountains, is seeking fortune in the city. Then, they organize another invasion. You can spend a lifetime living in this way.

MUSINGS OVER YERBA MATE

We get into father Bogdan’s open jeep and head back towards Lima, leaving behind a cloud of yellow dust that is hovering over the beaten road. The car bounces on stones. The paint coming off the vehicle very well corresponds with the muddy, grey, rocky landscape. After a few minutes, we come to a halt at a little bar or actually a shed made of a few planks and reeds patched together. There are several men here, seated at simple tables on wobbly wicker chairs. Some of them are talking, others are smoking. Two or three of them are staring blankly at the space in front of them or at the Havana Club drink quickly vanishing from their glasses. The faces are ravaged and unshaven. Hard work and daily struggles have carved deep lines on their cheeks and foreheads. It seems that they truly enjoy the short moment of relax and take delight in a glass of cold whisky or in a dispassionate gaze at the horizon. It reminds me of the words of Daphne Rose Kingma:

“The moment you are living through is exquisite in its uniqueness. It has never happened before. It will never happen again. Whatever you are doing – writing a book, watching a sunset, kissing your sweatheart, watering the zinnias, making love – allow yourself to receive the experience deeply. For to be in the moment is to be fully alive, to recognize at the level of your very cells that life itself, the weather, the clouds, the talents you possess, the people you love are utterly unique and absolutely unrepeatable. To live in the moment is to live. Live now!”

To quench my thirst, I choose a drink which is very popular here. Yerba mate tastes like unsweetened green tea. Apparently, the taste can be modified by the temperature of water used for brewing leaves. And it is not only the leaves that should be put into the wooden mug but also chopped palitos, the stalks of yerba mate. The tea is brewed with a special spoon, already placed in the mug, which also serves as a straw. After the first filling, the content of the cup swells, turning into thick suspension. Water, getting through to the bottom, gains an intensive, intoxicating aroma. Having finished the refreshing beverage, you can pour fresh water into the mug over and over again and take delight in its taste for as long as you wish. I’m happy when the drink washes away from my lips the flavor of dust and ashes that penetrate every nook and cranny here. Adding more water into the jug, I open the map of Peru. It has ragged edges. I try to go over the route to Machu Picchu, which is supposed to be a bit longer than just a flight to Cuzco and a railway journey to Agua Calientes. After all, the point is not to lose anything of the intoxicating taste of the adventure; intoxicating even more than fragrant yerba mate. This is why my finger touches a blue spot on the map. It is Titicaca.

ON THE ROOF OF AMERICA

The next day, I am again at the airport. My journey to Bolivia is quite complicated: first, I have to get on a plane to Arecipe, then take another plane to arrive at Juliaca and from there, by coach, reach the border in Casana. I leave excess luggage on the way, at a hotel where I am supposed to come back in a few days; wandering about at an altitude of four thousand meters with all that clobber does not make much sense. Breathing is difficult here but the air is marvelous – a bit chilly, crisp, crystal clear. After crossing the checkpoint, I can get into a bright yellow taxi and head toward Copacabana, a town with the population of a few thousand on Lake Titicaca. It takes half an hour to get there. The settlement has stretched its arms at the height of mere 3800 meters above the sea level. When the statue of Virgin Mary arrived here in the sixteenth century, the town turned into a pilgrimage center. Thefeast in honor of Our Lady, known here as Candelaria, starts every year on February 2nd. The festival, whose core is the presentation of native Aymara dances, resembles the carnival of Rio rather than a religious celebration. But there are some other peculiar customs here, too. It is enough to mention alasitas, a feast during which the faithful bring to churches miniature cars, houses, fields or other things they dream about to be blessed, asking the Lord to be soon presented with the full-size objects.

I get at the hotel which I had booked online. All inconveniences of the crazy journey that started at four thirty in the morning, when the sun was still asleep behind the horizon, are now compensated by the location of my apartment. A huge wall of glass opens up a view over the largest lake in South America, just a few meters away from its shore. It is impossible to imagine a more relaxing landscape. Taking in the view, I remember a myth I had once read, which said the Sun had been born right here, in the lake whose waters stand out so clearly against the grey stretches of the surrounding rocks. Moreover, the Incas believed that their first king, called Inca, emerged from the Rock of the Puma, that is from Titicaca – this is how the name of the lake should be translated.

After a short moment of contemplation, I can hear the telephone ring. The receptionist informs me that Guido, my guide, is waiting in the patio. He is a student of tourism. His face, revealing Indian features, is all smiles. Am I not too tired to set out for the exploration of the secrets of the town? – he asks in very good English. Of course, not, I answer. How could one go to sleep when so many nooks and corners of the city are waiting to be discovered? We plunge into the web of narrow streets filled with white houses and colorful, cosy shops. And Guido starts his tale.

It is not without reason that Bolivia is called the Tibet of the Americas – this is the highest and the least accessible country of both continents. That is where the idea of the fight for independence from Spanish domination was born, an idea which quickly gained popularity in other colonies. Peru achieved independence from Spain in 1824, but the territory of contemporary Bolivia remained under the rule of Pedro Antonio de Olañeta, a general faithful to the Spanish, whose resistance was only broken by the army of Simon de Bolivar. A year later, a new nation emerged and it was named in honor of its liberator.

Bolivia has often been described as a beggar sleeping in a golden bed. The amount of natural resources is incredible here, but they still remain unexploited; hence the country is counted among those five nations that are provided with the highest international assistance. This situation should come as no surprise – it is enough to have a look at education: more than twenty per cent of women are still illiterate.

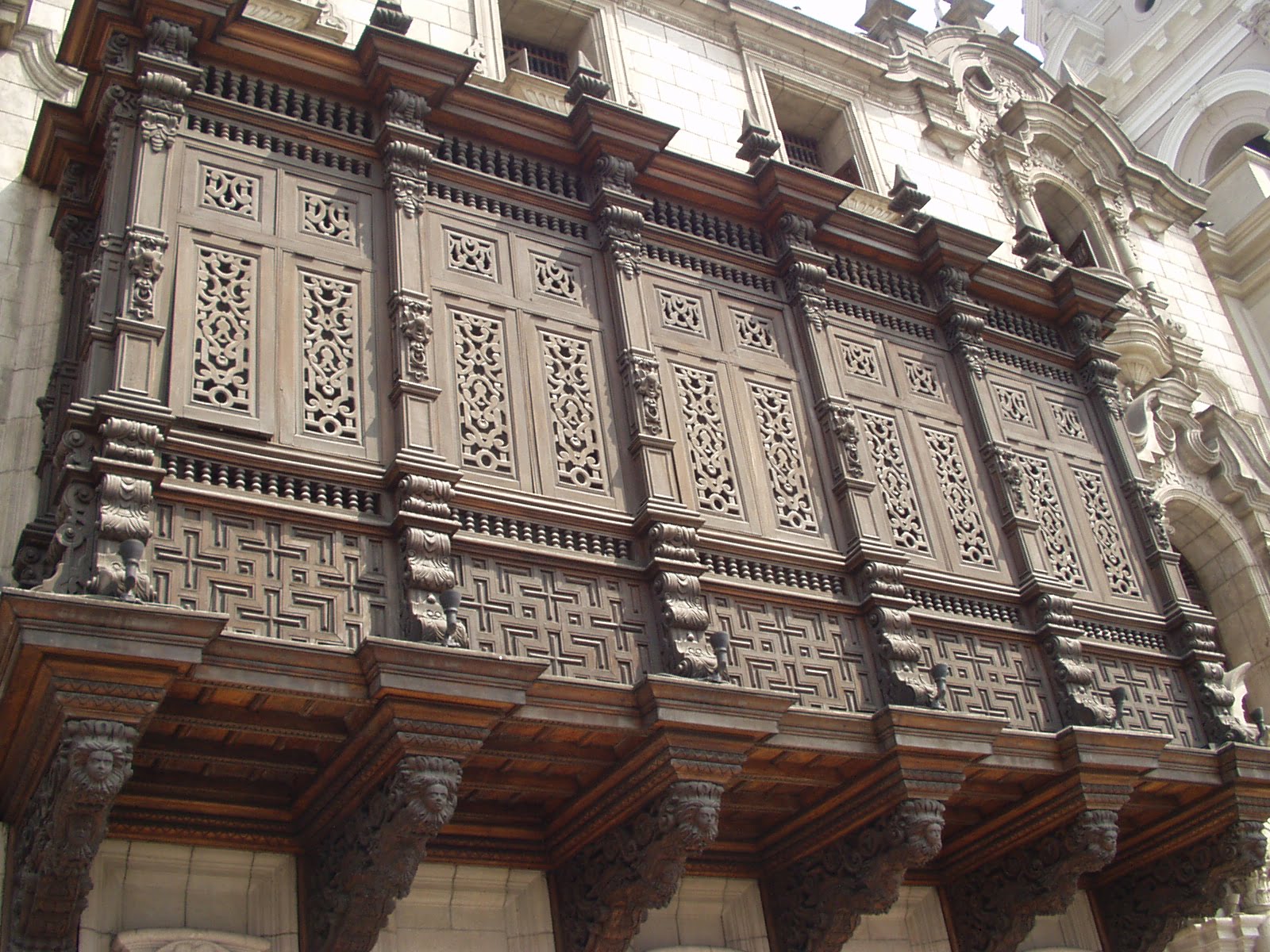

The vicinity of Titicaca is full of mysterious remnants of ancient cultures, starting from Tiwanaku and ending with Inca culture. Their traces can be found both on the shores of the lake and on the islands covered with ebullient vegetation. The remains of an astronomical observation center dating back to pre-Columbian times has been discovered in Copacabana. The town used to be a harbor for pilgrimages heading for the Island of the Sun and the Island of the Moon. In mystical atmosphere, pilgrims set off in tiny little canoes to worship gods who had chosen the islands on Lake Titicaca as their home. Today, in the middle of the former Incan waka, the place of worship, there is a church dedicated to Our Lady of Copacabana with the figure chiseled by an Indian sculptor, Francisco Tito Yupangui. The white building is crowned with fancifully carved columns, the stone altar covered with silver and gold which are not very difficult to obtain here since the Andes abound in the mines of those precious metals. The sculpted figures are clad in robes adorned with precious stones. The sight seems quite bizarre for a European accustomed to stately Gothic churches.

The majestic building of the church contrasts with a newly-built sports center. There is a green football pitch here, there are volleyball and tennis courts, and a white swimming pool. There is also a ring where the Bolivians can play their national sport – here, they tend to do it in a controlled manner but it is not always so. Tinku, a Bolivian tradition, is a ritualistic fistfight which is supposed to grant leadership in the group to the winner. Annual fights are held in the town of Potosi in the north of the country. Casualties are multiple, especially among the drunken participants of the absurd combat. And women are not excluded. In theory, the only weapon are supposed to be human fists, but stones and knives are not uncommon.

What comes to my mind when we walk past the golf course is a story about an Argentinian champion of this discipline. Is it true? I don’t know, but it is certainly eye-opening. They say that when Robert de Vincenzo had won a tournament and received an adequate check, he was interviewed by a few reporters and then tried to find his car in the parking lot. He was approached by a young woman who first congratulated him on his victory and then complained that her child was terminally ill. Of course, she had no money to pay for hospital treatment. De Vincenzo took a pen out of the pocket and wrote on the check his interlocutor’s name. A few days later, one of the golfer’s friends, having heard the story, walked up to him at the club and said:

‘I’ve heard that last week after the tournament you met a certain woman and gave her a check.’

De Vincenzo nodded.

‘Well…’ the man sighed. ‘I have bad news for you. It’s a crazy person who often hangs around the club. She doesn’t have any child. She doesn’t even have a husband. You were just cheated.’

‘Does this mean that she doesn’t have any fatally ill child?’ De Vincenzo asked, making sure he understood everything correctly.

‘That’s right’

‘But this is the best piece of news I’ve heard today!’

We move on, Guido and me. Behind the sports center, on one side, the road goes down to the lake. We take it to get to the harbor, walking past dozens of little shops owned by dark-skinned women in broad-brimmed hats and traditional, colorful, bright clothes. On the shore, we buy a ticket for the next day for a morning cruise to the Island of the Sun.

tłum. M. Konopko

Polub stronę na Facebook